When it came time to write a fitting tribute to Jim Morrison, leader of The Doors, who died on this date in 1971, I knew that there wasn't a better man for the job than frequent FH contributor, Harvey Kubernik.

Harvey lived thru The Doors' era, experiencing the band first hand at the peak of their popularity. He also had the insight to watch them grow in the ranks ... and the opportunity to interview the surviving members on numerous occasions after Jim's passing.

The Doors left behind a musical legacy that stands on its own.

Harvey's book, "The Doors: Summer's Gone" tells the story of the band in their own words, in many cases as it happened. Their closest associates also weigh in and the book presents a fascinating look inside the making of the band. It is HIGHLY recommended.

Who better then to lead us down the path of saluting Jim Morrison and The Doors?

Our piece presented today is a HIGHLY edited portion of a MUCH longer article that Harvey has put together. You can look for it in Music Connection in its unedited form ... (the whole thing runs around 18,000 words ... so pour yourself a tall one before sitting down to take it all in!) ... as well as a 12-page spread running in Ugly Things Magazine later this month.

Meanwhile, this edited piece works just great for OUR purposes ... it perfectly captures the mood and the time that was The Doors at their very best ... and their very worst.

Jim Morrison was a complicated man. I'm not sure that he ever fully measured up to his own expectations. Many factors got in the way of this ... but when you break it all down (break on through to the other side?) you find that in most cases Jim was his own worst enemy.

Enjoy now, this Forgotten Hits Exclusive, courtesy of Harvey Kubernik, who tells the story of Jim Morrison and The Doors ... in the words of those who were there at the time living it. (kk)

James Douglas Morrison

(December 8, 1943 Melbourne, Florida-July 3, 1971 Paris, France)

By Harvey Kubernik Copyright 2021

During 1966 I was at my friend David Wolfe’s house on Selmarine Drive in Culver City California when Jim Morrison of a new band called the Doors appeared on 90 minute 10:00 pm talk television The Joe Pyne Show on KTTV channel 11. We both seem to remember the confrontational host in a heated dialogue with Morrison in Pyne’s Beef Box.

I first heard the Doors at Fairfax High School in West Hollywood on Burbank-based AM radio station KBLA on deejay Dave Diamond’s Diamond Mine shift. He constantly spun the acetate of their debut long player in late December 1966 before the official January ’67 album release.

The erudite radio broadcaster explained the origin of their name from the title of a book by Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception, derived from a line in William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

I loved when Diamond segued from “Soul Kitchen” to “Twentieth Century Fox.” Some of it sounded like the music they had on KGFJ-AM my R&B channel and KBCA-FM, the jazz station. “Break on Through (To the Other Side)” reminded me of Ray Charles’ “What’d I Say” from the 1963 Kenny Burrell and Jimmy Smith jazz arrangement recording of his tune on the Verve label.

I purchased The Doors in monaural on the Elektra label that January of 1967 at The Frigate record shop on Crescent Heights and Third Street. I had no idea as a teenager that The Frigate was literally right near the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi-founded Third Street Meditation Center where Ray Manzarek initially met John Densmore and Robby Krieger in 1965, then introducing the duo to his buddy Jim Morrison.

I then saw the Doors in January, 1967, on the Casey Kasem-hosted afternoon television show Shebang! In July I caught the Doors on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. I danced occasionally on both Hollywood-based programs 1966-1967.

On April 9, 1967, my cousin Sheila Kubernick telephoned me very late at night. She had just returned from The Cheetah club in Venice and witnessed the Doors in person. Sheila, a Cher-lookalike at the time, was still in a trance, courtesy of Jim Morrison. Shelia later drove my brother Kenny and I to the Valley Music Center for a concert by the Seeds still reminiscing about the Doors.

I went to the Doors concert at the Forum in Inglewood, California on December 14, 1968. On the show were Jerry Lee Lewis, Sweetwater, and Tzon Yen Luie, who performed with a Chinese stringed instrument the Pi pa. I remember as a teenager watching Lewis’ Forum set opening for the Doors where he received a mixed response. I recall The Killer jumping on top of his piano and kissing off the crowd. “For those of you who liked me, God love ya. For the rest of you, I hope you have a heart attack!” Years later John Densmore told me that the Doors initially wanted Johnny Cash for their Forum booking but the promoter said no because “Cash was a felon.”

Over the decades I conducted multiple interviews with Ray Manzarek, John Densmore, and Robby Krieger, who were always accessible and generous with their time and responses. I interviewed Bruce Botnick, Jac Holzman and Paul A. Rothchild.Over the last 47 years I’ve conducted numerous interviews with Manzarek, Densmore and Krieger and intimate associates of the Doors for published articles since 1974 and display in my books this century. I’ve also discussed the Doors with friends, and Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees who saw the group in performance.

My focus on the Doors has always been on the recordings, music, lyrics and the sonic mission of the band, not Morrison’s omnipresent legal problems and his death in Paris coverage.

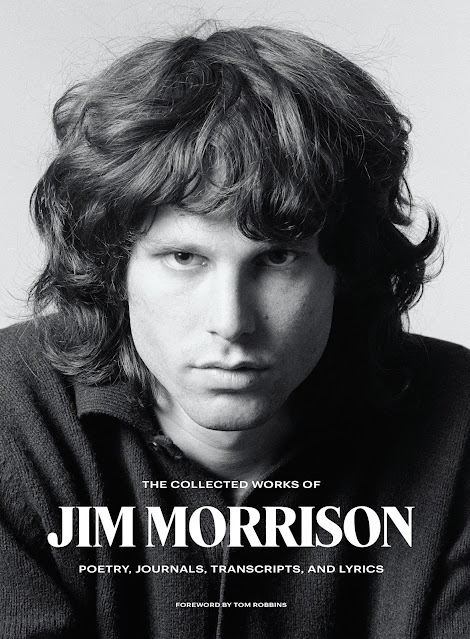

It’s now 50 years since James Douglas Morrison left the physical world. In June 2021, Harper Design, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, published The Collected Works Of Jim Morrison-an almost 600-page anthology of his writings.

Forgotten Hits has asked me to provide some insights exclusively from my archives into Morrison’s life with the Doors and their cultural achievements for FH viewers and readers.

The below texts are edited and culled from some previously published and never exhibited dialogues coupled with 2021 reflections on Morrison and his fellow band mates.

*****

Ray Manzarek Raymond Daniel Manzarek (born Raymond Daniel Manczarek) was born in Chicago, Ill. Ray resided with his family on the South side of Chicago and graduated DePaul University with a B.A. degree in economics. In the early 1960s the Manzarek clan relocated to the South Bay Redondo Beach community in Southern California. It was in Westwood, California in the campus of UCLA in 1964-1965 where keyboardist Manzarek first met writer James Douglas Morrison, a transfer student from Florida State University. At the UCLA Film School, Ray earned a master’s degree in Cinematography and Jim a B.S. degree in the Theatre Arts department of the College of Fine Arts. While performing with Ray and the Ravens in the summer of 1965, Manzarek saw Morrison again at Venice Beach and they discussed forming a band together. In 1965 Ray was introduced to Richard Bock, owner of the monumental World Pacific Records. Rick and the Ravens cut a few promotional singles for World Pacific’s Aura Records, the rock subdivision. On March 26, 1965, the group appeared on the Marvin Miller-hosted Screen Test on KCOP-TV channel 13 at 10 p.m.

Bock led Ray to Los Angeles, where he encountered Los Angeles natives, drummer John Densmore and guitarist Robby Krieger.

Densmore, a graduate of University High School went to Santa Monica City College and San Fernando Valley State College. Krieger, from Pacific Palisades High School attended U.C. Santa Barbara and then UCLA. Densmore and Krieger had briefly been in a group called the Psychedelic Rangers in 1965.

In early September ’65, Ray Manzarek, his brothers Jim and Rick, Jim Morrison, John Densmore and a bass player named Patricia Sullivan recorded a demo in lieu of another single session date at Bock’s World Pacific studio on Third Street in West Hollywood.

Their acetate results were “Moonlight Drive,” “My Eyes Have Seen You,” “Summer’s Almost Gone,” “Hello, I Love You,” “End of the Night” and “Go Insane.”

In October, Ray revamped the Rick and the Ravens lineup, added Robby Krieger and along with Morrison and Densmore, they became the Doors.

Determined band members dropped off the acetate to record labels in town: RCA, Capitol, Liberty, Decca, Dunhill and Warner/Reprise all rejected them.

Eventually it caught the attentive ears of Billy James at Columbia Records, where the Doors had a short-lived stay before finding permanent residence at Elektra Records, the home of the brotherhood 1966 until 1971.

Q: You and Jim went to the UCLA film school and students in the motion picture division. You had a class with the French director Jean Renoir.

A: Jim came from Florida, I came from Chicago. We smoked pot together, we talked philosophy together. We had a class with the German director Josef von Sternberg. This was in 1965. Von Sternberg, the great German director of Marlena Dietrich, who did The Blue Angel, Marocco and Shanghi Express. Having Von Sternberg seeing the deep psychology of his movies, and the pace at which he paced his films, really influenced Doors’ songs and Doors’ music. The sheer psychological weight of his movies on what we tried to do with our music.

The film school is always there. Our song structure was based on the cinema. Loud. Soft. Gentle. Violent. A Doors’ song is again, aural, and aural cinema. We always tried to make pictures in your mind. Your mind ear. You hear pictures with the music itself.

He’s the guy

who really kind of gave a real sense of darkness to The Doors, not that we wouldn’t have

been there anyway. But having Von Sternberg seeing the deep psychology of his

movies, and the pace at which he paced his films, really influenced Doors’

songs and Doors’ music. The film school is always there. Our song structure was

based on the cinema. Loud. Soft. Gentle. Violent. A Doors’ song is again,

aural, and aural cinema. We always tried to make pictures in your mind. Your

mind ear. You hear pictures with the music itself.

In 1965 we graduated. Jim got his Bachelor’s degree, I got my Master’s degree – and we were hopefully going to do something together. But Jim said he was going to New York City. I thought, ‘Well, that’s it. I’ll never see Jim again.’

Q: I walked with you on Venice Beach many years ago and you pointed at the sand and said, ‘This is where Jim sang the lyrics to ‘Moonlight Drive’ to me in a Chet Baker-like voice.’

A: When I first heard Jim sing in Venice I thought he had it. Interestingly, on ‘Moonlight Drive’ that is really a seminal, or a signpost song. I thought it was brilliant. His voice had a softness to it. It’s the first song Jim Morrison sang to me on the beach. It had been after we graduated UCLA and I ran into him on the beach. ‘What have you been doing?’ ‘I’ve been writing songs.’ ‘Sing me a song.’ ‘I’m shy.’ ‘You’re not shy. Stop it. There’s nobody here. Just you and me. I’m not judging your voice. I just want to hear the song. Besides, you used to sing with Rick and the Ravens at the Turkey Joint West in Santa Monica and did ‘Louie Louie’ until you could not talk.”

Q: I know Jim played tambourine one evening with Rick and the Ravens when you were booked with Sonny & Cher at a high school event, the duo never showed up. Jim said that was the easiest $25.00 he ever made. And then he went into a garage rehearsal room with the Doors. Was Jim a natural front man at the Turkey Joint West?

A: No. (laughs). It took a while and later to work it out on stage at The London Fog and Whisky A Go Go. But by God, he sure did scream a lot and sure had a willing injection of energy into rock ‘n’ roll.

Q: Before the Doors inked a record deal in 1966 with Jac Holzman and his Elektra Records, in December of 1965 the Doors had a six month provisional contract with Columbia Records. Billy James, the former publicist for Columbia was now the manager of Talent acquisition and Development for Columbia. The label never assigned a producer or even committed to a recording session.

A: Without Billy James the Doors would have never made it. On my God! I got my Vox Continental courtesy of Billy James. He heard the original rough Doors’ demo and said, ‘you guys got something. You’re going all the way.’ Jim dropped off the acetate at Columbia.

Billy said, ‘Welcome to Columbia Records. Is there anything we can do for you guys?’ And we said, ‘Yeah. You can give us some front money. Do we get paid for signing?’ ‘No, we don’t do that. Do you need any equipment?’

At the time I was playing my brother Jim’s Wurlitzer keyboard. On the demo it was a piano. Columbia had just bought up Vox. Billy offered, ‘You want a Vox Continental Ray?’ ‘Yes!’ Every English group plays one. The Animals, the Dave Clark 5, Manfred Mann. ‘Go out to the Vox Plant in the San Fernando Valley. It’s right across the street from the Budweiser Plant.’

We jump in John’s van and see what we pick up. Robby gets an extra guitar. And we got two amps with 14 inch speakers. We went around to the loading dock and picked up the stuff and got out of there like bandits.

Q: And Billy eventually joined Elektra Records in 1967. Let’s discuss your debut LP The Doors. It was done at Sunset Sound with producer Paul A. Rothchild and engineer Bruce Botnick.

A: Sunset Sound was a very hip recording studio on Sunset Blvd. The Beach Boys had been there. Herb Alpert, Love. It was owned by a trumpet player, (Salvador) Tutti Camarata and he had the Camarata Strings, I believe. It was an excellent recording studio, four tracks. Rothchild and Botnick. Paul was the producer.

Rothchild and Botnick are Door number 5 and Door number 6. There’s four Doors in the band and two Doors in the control room. So, they were always there, always twisting the knobs and really on top of it. A couple of high IQ very intelligent guys. We couldn’t have done it without them.

Paul Rothchild was the guy who had produced The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and also Love, along with Botnick. The two of them did those albums together. So, Robby was a big fan of the Butterfield Blues Band and he was very excited that Paul Rothchild was gonna produce for us. I didn’t know either one of them and not familiar with their work outside of Love. I had heard Paul Butterfield and thought it was good. Chicago blues by Chicago white boys. Being a Chicago white boy myself I could identify with Chicago white boys playing the blues. So it was a great combination of six guys. That first album was basically the four Doors and the two other Doors in the control room making the sound. We made the music. They made the sound. And they did an absolutely brilliant job. And it was a real joy and a great learning experience.

I had been in a fabulous recording studio before at World Pacific on 3rd Street in L.A. with Rock and The Ravens for Dick Bock. And that’s where we cut The Doors’ demo, along with some Rick and The Ravens songs.

Rothchild and Botnick were two alchemists with sound. We were the alchemical music makers but they were alchemists with sound-adding a bit of this-a bit of that. Some reverb. Some high end. Let’s hit it at 20k or 10k. Let’s dial in a bit of bass in there. They were making this evil witches brew concoction as we went along. And the sound just got better and better.

Q: Though several bassists auditioned for the group, none could match the bass lines you provided by your left hand employing a Fender Rhodes keyboard bass instrument. Left hand bass, and your right hand you were not doing chords but comping on the organ or piano. I always felt that was one of the main attractions about the sound of the Doors and the dynamic of the Doors sonically. And not having another physical fifth person on stage as bassist as you held down two instruments … although you had a bass player on some recording dates.

A: First of all, the left hand created that hypnotic Doors’ sound. For instance, during the ‘Light My Fire’ solo section, it’s an A-minor triad to a b-minor triad that just repeats like (John) Coltrane’s ‘My Favorite Things.’ The same sorta modal chord structure that Coltrane used in ‘My Favorite Things.’ Left-handed I’m playing the same thing over and over. The right hand is just playing filigrees, comping behind Robby Krieger, punctuating with chords, punctuating with single notes playing with Robby Krieger. When I’m soloing, I’m playing anything I want to play. And that bass line just keeps on going. It never varies and it never stops. Over and over like tribal drumming or Howlin’ Wolf playing one of his songs without any chord changes. On and on and on. The same pattern. Now, if I were to have added a live bass player to play that the guy after about 2 or 3 minutes playing the same two triad … I’ve had guys say to me, ‘I can’t do this Ray…’

The same three notes over and over. And off he goes, man. So I think the secret to the Doors hypnotic sound comes out of the left hand keyboard bass. Meanwhile the right hand thinks its Johann Sebastian Bach.

A fifth person, another physical element on stage, would have made it not a diamond. It would have taken away the diamond with Morrison at the point. As we faced the audience Morrison is at the point, (John) Densmore is at the point, behind Robby and I, who are point left and point right, a four-sided diamond, the purity of the diamond shape rather than some kind of pentagram star thing. And a fifth element would have confused it. Another guy playing would have made a more confusing bottom.

Q: And yet, on many subsequent sessions you were joined by a studio bassist who essentially followed and copied your bass lines done on the Fender Rhodes.

A: I was the bass player of The Doors. When it came to recording I played a Fender Rhodes keyboard bass. The instrument was great in person because it had a deep rich sound and moved a lot of air. But in the recording studio it lacked a pluck. It did not have the attack that a bass guitar would have-especially if you played a bass guitar with a pick. You had plenty of attack. So, on some of the songs we brought in an actual bass player, one of the Los Angeles cats, Larry Knechtel. Who played the same bass line that I played on ‘Light My Fire,’ who doubled my bass line. They could then get rid of my bass part and use the nice sound that Larry Knechtel could get. The click and the bottom.

Q: And, in the sound mix the keyboard was treated equally. Not a second thought overdub or hidden below in the collaboration.

A: Well it had to be. We were the Modern Jazz Quartet!

Q: You then start “Strange Days” L.P.

A: Album two is recorded on an eight-track. The first album was four-track. We now had four more tracks. That meant everything that we could do on the first album We would still have four more tracks left over for overdubs. For experimentation. So we experimented in and out of the universe. I actually played one of the songs backwards. The song was played to me backwards and I had each bar written out with the chord change that went along with it and I started reading the music on the lower right hand side and read right to left across the bottom line. And then jumped to the next line, when I got to the end of the previous line, jumped to the next line up on the right hand side, reading everything backwards, bottom to top, getting closer and closer, finally to the top line and hoping that I end when the song begins. ‘Cause it’s all going along and it’s backwards. I’m following (John) Densmore’s beat on the bass drum not knowing what’s going to happen. And sure enough, I get to the last measure here are four more beats! I stopped and the music stopped. It was a miracle. And everyone went, ‘You did it Ray!’ And I went to the guys and said to them in the control room. And I said, ‘Please, whatever you do, help me here, never let me do his ever again.’ And they collectively said, ‘That’s a deal, Ray.’

Q: You saw the studio becoming a laboratory.

A: Exactly.

It was a place where we could really experiment. We could

put on our lab tech coats rather than coming in with our

‘Mod’ outfits. It’s almost as if we put on our glasses. I felt

like I was in a 1932 German Science Fiction movie, ‘Woman

In The Moon,’ something along that line. Some Fritz Lang. It

was like ‘Metropolis’ and we were wearing those glasses

that you wear so you don’t get sparks in your eyes and we

had lab coats on. And we were preparing this strange

concoction called ‘Strange Days.’

Q: You had already had some of the songs for it like

‘Moonlight Drive’ from 1965, ’66, and now in 1967, it’s

coming to fruition in the studio. Plus, Jim

Morrison’s voice really went further and deeper on the

“Strange Days” expedition.

A: Well, the man had his chops as they say. Jim got his chops together. He had a thick bull neck resembling a large engorged male organ. (laughs). And by then, he could sing, man. That throat had opened up and that man was singing.

I knew Jim was a great poet. There’s no doubt about that. See that’s why we put the band together in the first place. It was going to be poetry together with rock ‘n’ roll. Not like poetry and jazz. Or like it, it was poetry and jazz from the ‘50s, except we were doing poetry and rock ‘n’ roll. And our version of rock ‘n’ roll was whatever you could bring to the table. Robby bring your Flamenco guitar, Robby bring that bottle neck guitar, bring that sitar tuning. John bring your marching drums and your snares and your four on the floor. Ray bring your classical training and your blues training and your jazz training. Jim bring your Southern gothic poetry, your Arthur Rimbaud poetry. It all works in rock ‘n’ roll. So Jim was a magnificent poet. I loved his poetry. The fact that he was doing ecological poetry. ‘What have they done to the earth?’

Q: Jim Morrison was the best man at your wedding to Dorothy Fujikawa at Los Angeles City Hall.

A: Jim Morrison and Pamela Courson and the two of us went down to City Hall to get married. And the bridesmaid was Pam and the best man was Jim. And we had our celebratory luncheon on Olvera Street where we had enchiladas and margaritas. And the next night we played the Shrine Auditorium with the Grateful Dead. Psychedelic, man.

Q: Your record producer, Paul Rothchild.

A: Paul Rothchild was a stone cold intellectual. A fan of Bach. Out of New York City. One of the most intelligent guys I ever met in rock and roll. Great ears. Rothchild had two types of marijuana. Paul had these little vials. One was called ‘work dope’ and the other was ‘playback dope.’ ‘WP.’ Was not too strong, you could get a little buzz, a little mellow and enter into a proper space and you had your wits about you and had your energy, and could play your instrument. And then after the evening’s recording you could sit back and have something a little bit stronger. This is the listening dope. Light up a joint, have a couple of puffs. Doors weren’t pot heads or dope addicts or anything.

All it took was a couple of tokes and you were stoned. ‘Now let’s hear what we’ve done.’ And we would give it the pot test. The takes that passed the pot test are the ones that stuck around. They are still on the albums. We mixed ‘Your Lost Little Girl’ on some hash.

Jim Morrison rolled the best joints. I rolled one that was flat and crushed, semi-round and loose. It was impossible to smoke a Ray Manzarek joint. That’s why I had to have a pipe I could smoke it on my own. Morrison had the ability to take a single sheet of rolling paper and he rolled a joint that was absolutely perfect. Like a thin cigarette. ‘How did you do that?’ Ray…It’s one of my God-given talents.’ ‘You are amazing, man.’ The tightest, amazing and cleanest joint, like a half size cigarette. The length of cigarette and the diameter was half the size of a regular cigarette. How he did it I’ll never know but it was always a pleasure to smoke a Jim Morrison joint.

My God, Strange Days, what an album cover. We told the art director from

Elektra Records, Bill Harvey, ‘Make something ‘Fellini-esque.’ And he did that on

his own. That’s all we told him. We saw the photos and said, ‘Bill this is

fabulous. You’ve outdone yourself.’ And Bill said, before he died, ‘That’s the best

album cover I ever did.’

Q: What is the magic of the durability of the sound of the Doors that still resonates today even more than ever before?

A: Pure serendipity. It was an energy of the time. Morrison had a great line, ‘in that year we had an intense visitation of energy.’ That years lasted from approximately 1965 to 1970. The psychedelic generation had come of age. The young people had come of age. We were the fruit of the American dream. We had everything. All the education and all the pampering. Low and behold, we are all one with everything. Everything is one with us. We, especially the hippies, are all each other’s brothers and sisters. Now let’s become artists and let’s see if we can change the world. Let’s see if we can take love and make love change the world.

So, what happens with the playing of Doors’ music you enter at a lower state of consciousness into an almost hypnotic state and at the same time an elevated cosmic state of consciousness. So you are comically aware and you are hypnotically down into the vibrations, the energy of the telluric force, the energy of the planet, the energy of the thousand miles an hour spinning globe that we’re on. With that hot molton center. You’re part of that and you’re part of the infinite cosmos at the same time. All in playing you music. And that’s what Doors’ music is about. It’s right there.

Q. Why do Jim Morrison’s lyrics work so well in recordings and the printed page?

A. Well, you know, lyrics are poetry. The words were well edited. Jim was good that way when it came to songs. When you are doing this written poetry you can really stretch out and you can really expand. And, no one so far has done an ‘Ezra Pound’ on Jim Morrison. With his poetry, he’d throw this out, take this line, or two lines, but when it comes to music you gotta be very choosy because you only have a short period of time. Songs in a way, outside of like ‘The End,’ and ‘When The Music’s Over,’ are sorta like haikus. The fit has to be very tight. I saw Jim’s words before he started writing songs. So, when you see his words on the page that’s poetry. I always thought of Jim as a good poet. But when he started writing songs, then everything became verse, chorus, verse chorus. Really tight, and it was a whole other ball game. He put his words into an entirely different context. A musical context. A hit single in a three-minute context. I thought ‘Moonlight Drive’ was brilliant.

Q: The “Waiting For The Sun” album. Some songs already

existed in raw form but a lot of new material was written

for this endeavor.

A: You know it’s time to do a record when you have 10 or

12 songs together. I mean, when we would get together in

the rehearsal studio they were polished. They were

changed. They were adapted. Somebody, invariably Robby

or Jim who would come up with the original idea. But boy,

the four of us would get together, change and modify and

polish the songs.

Q: “Hello, I Love You” from “Waiting For The Sun” had been

around for a while.

A: Yes. It was a song Jim wrote on the beach when we used

to live down in Venice. Dorothy would go off to work and

Jim and I would go off to the beach around the rings on the

sand at Muscle Beach and work out around the bars, rings

and swings and get ourselves into physical shape. He was

gorgeous. Man, he was perfect. He was a guy who had

opened the doors of perception and made a blend of the

American Indian and the American Cowboy. He was the

white Anglo Saxon Protestant. The WASP who had taken on

the mantle of the American Indian. He now was no longer

a fighter of Indians. He was a lover of American Indians.

Like John F. Kennedy, that guy would have been a great

President. Pre-alcohol, would have been a great President.

The alcohol unfortunately destroyed Jim Morrison.

On 'Waiting For The Sun,' we were working in the future space.

The Doors on their third album were in the future. And many

things have come to pass that Jim Morrison wrote about.

Q: We are then lead into “The Soft Parade.” Was there a pre-

production meeting where everyone voted to include the use

of strings and horns on the album?

A: We had made three albums with the same formation and at

some point or another when you make albums you want to

do an album with expanded sound, so you want to have

some horns and strings. My God, everybody did it. And we

were gonna do it, too. I want some strings. I want some

jazz arrangements. I want some classical arrangements.

And everyone said yes. Great idea. And a record label that

said it was fine. What was great about the record label was

that Jac Holzman said, ‘Boys, do whatever You want. Just

don’t use the seven illegal words.’ George Carlin’s seven

foridden words. Other than that, anything goes. What ever

you want to do. And Paul Rothchild encouraged it.

Q: George Harrison dropped by one of your ‘Soft Parade” sessions.

He was visiting the Elektra studios. He mentioned all the musicians

at your date reminded him of The Beatles’ “Sgt. Peppers” because

of the orchestra booked.

A: Yes ... A Beatle in the room. A very charming guy. Very low key.

And I’m surprised John Densmore didn’t become good friends with him.

Q: And, again, the Morrison vocals are potent, distinctive and his voice

more confident than ever on the 'Soft Parade' album.

A: He’s no longer a blues singer. He’s added Frank Sinatra crooning to his

voice and did a brilliant job. Terrific. Girls loved it.

JOHN DENSMORE: Jim had an astounding baritone. Un-schooled. It was luck. It was

fate. He never sang before I saw him in the garage. It was kinda squeaky in the early

days. He just was afraid to open up. How audacious. “OK. I’ve never sung and I’m

gonna be the lead singer of a rock band.”

Q: You also had individual writing credits for the first time on the album sleeve.

A: That’s a great story. Because of ‘Touch Me.’ The song was initially called ‘Hit

Me,’ and Jim is gonna say hit me. It’s ‘Hit Me’ like in poker. And Jim said, ‘No it’s

not like poker. It’s like someone is gonna walk up to me and are gonna hit me.

You gotta change the line.’ ‘To what?’ ‘Touch Me.’ Beautiful. And along with

that ballad part he sings in ‘Tell All The People’ the line with ‘Get your guns …

Follow me down.’

Morrison, a military boy said, ‘I am not going to say that.’ And

Robby replied, ‘That’s the way I wrote it and you can’t change it.’ Robby was going

to stand up to Jim at that point. And Jim said, ‘I am not going to do it.’

And Robby said, 'Well, that’s the song.’ And Jim said, ‘We’re gonna have to say that you wrote this song.’

And Robby said,

‘OK. Fine with me.’ And that lasted for one or two more albums.

Q. And, guitarist Robby Krieger was another kind of songwriter. He penned a lot of the popular radio hits and chart singles. “Love Me Two Times,” “Spanish Caravan,” the lyrics to “Tell All The People,” “Touch Me,” “Runnin’ Blue,” “Love Her Madly,” and co-wrote “Peace Frog” and “Light My Fire” with Morrison.

A. Robby was a different sort of lyric writer. You know, Robby might be the secret weapon of the Doors, we get this great guitar player who plays bottleneck, and all of a sudden he comes in and plays ‘Light My Fire,’ the first song he ever co-wrote with Jim. And then Robby wrote ‘Love Me, Two Times,’ ‘Love Her Madly.’ ‘Touch Me.’ Lots of Doors’ hit singles. Another guy with a high IQ.

Q: And by ‘The Soft Parade” Jim Morrison started to indulge and really drink.

A: Jimbo came out. They call it the demon rum. There’s a demon in the bottle.

And there’s a demon in that white powder, too. A demon on the blade. You know

what those things do? They open the trap door of the subconscious and allow

some creature to come out. And the alcohol for Jim, a genetic pre-disposition

to alcohol, something came out, man. Some kind of combination.

He went from being the poet to a shooter. Shooter Morrison. I was flabbergasted.

While you can see that Jim Morrison is undergoing a transformation. Right before

our very eyes. And I hoped that this transformation was short lived. But it wasn’t.

‘This can’t last. This is not Jim.’

We started experimenting in the studio. I wouldn’t allow anything to get out of

the recording studio without my approval. If I didn’t think it was right it did not go

a record. Nothing happened without my OK. We did some composite vocals. You

do what you have to do. If Jim sings one line great. Fine. Then let’s get the next

line. Let’s get the words, man. Whatever it takes to get the best possible

performance. The Soft Parade’ song is an unusual piece of music. It’s a suite

Q: Then we have "Morrison Hotel.”

A: Well, we had done out horns and strings experimentation.

We had had a great time. I had a great time.

Critically it was our least acclaimed album. However, it has stood

the test of time and there are many great songs on there. So, you know what?

We’ve done that experimentation. Let’s go back to the blues. Let’s get dark and

funky. Let’s go downtown for the album cover. We went to the Hard Rock Café on

skid row with (photographer) Henry Diltz. And we went to a flophouse called

The Morrison Hotel. Rooms A sign read $2.50 and up. It was definitely supposed o

be a funky album and you can see that on the inside photo and the front and back.

Album covers were always important. We were involved heavily in that process.

You could never just turn it over to the record company. Everything that the Doors

turned out had to be stamped by the Doors. We approve of this.

Q: There’s a song called ‘Waiting For The Sun’ on “Morrison Hotel.”

A: We loved the title. But the song had not come together earlier. We finally got it

beautiful piece of music. It needed to cook more. Sometimes Doors’ songs came

out of the collective conscious whole. ‘Bam. That’s it.’

Others needed to cook and they needed be worked on.

And ‘Waiting For The Sun’ one of those songs with a great title.

Q: It’s a hard mean album. Morrison’s voice lends itself to this specific material.

A: It was a barrelhouse album and barrelhouse singing. He’s smoking cigarettes.

‘Jesus Christ, Jim. Do you have to smoke cigarettes and drink booze?’ He didn’t

say it but it was like, ‘This is what a blues man does.’ Oh fuck. That’s right.

Q: How could Jim Morrison with his Dionysian demeanor write and suggest instruction or guidance lyrically in that song, “Keep your eyes on the road your hands upon the wheel,” when most of the time he certainly didn’t operate or drive a car like this himself?

A: Well that was the better Angel. That’s Jim Morrison. Not Jimbo. Jimbo was the guy who took Jim to Paris and said, “let’s go and die in Paris.’ We’re going to have a death in Paris. Like Thomas Mann’s novella Death In Paris. That was Jimbo.

Q: Then there is the tune “Peace Frog.” In 1995 you told me for Goldmine magazine, “Blood in the streets in the town of Chicago” is obviously about the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. It was written after the young people rioted against the war, in Vietnam.”

A: Those are great lines. Morrison goes further to say, ‘Blood is the rose of mysterious union/blood will be born in the birth of a nation.’ So it’s the idea that blood is the cleansing property, and from blood will come the healing and the enlightenment of the nation. America is what Jim is singing about. ‘Birth of a Nation.’ Another cinematic reference.

Q: Just before the album “L.A. Woman” formally began, producer Paul Rothchild leaves the project.

A: Yes. He did a great service to us. We played the songs in the studio so Paul could hear what the songs were. First at the rehearsal studio and then over to Elektra. I think we went back to Sunset Sound, too. We were bored. He was bored. We played badly. And Paul said, ‘you know what guys? There’s nothing here I can do. I’m done. You’re are gonna have to do it yourselves.’ And he walked out the door. We looked at each other and said, ‘Shit. Bummer.’ And Bruce (Botnick) said, ‘Hey, I’ll do it! I’ll be the producer.’ John (Densmore) said, ‘We’ll co-produce with you.’ Bruce said, ‘That’s a deal. Let’s all do it together.’ And then Jim said, ‘Can we record at our rehearsal studio?’ And we all said, ‘Hey, we play great at our rehearsal studio. Let’s do it..Can it be done?’ And Bruce said, ‘Of course I can do it there. I’ll set the board up and a studio upstairs. You guys record downstairs. That’s where we make the album and it will be virtually live. ‘Yea!’ And we got excited like that Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland ‘Let’s put on a show!’

Q: And, Jerry Scheff plays bass on ‘L.A. Woman.’

A: Botnick brings in a guy who is going to be playing with Elvis Presley. ‘I got Elvis Presley’s bass player.’ ‘Shit, man.’ He came in. A very cool guy who is playing with Elvis Presley.

Q: And, you and Jim just earlier had watched the “Elvis Presley 1968 Comeback Special” on television. I wrote the liner notes in 2008 for the CD reissue. Elvis is wearing leather on that program. And I believe Jim had his leather pants made on Sunset Blvd. in 1967 or in ’68.

A: Yes. We watched it. Elvis puts on his Morrison outfit. (laughs). He had seen Morrison. He knew what he was doing. Imitating Jim.

Q: “L.A. Woman” is a logical step from “Morrison Hotel.”

A: I think it’s the same Doors but a continual growth, continual evolution of The Doors. Continual revolution of The Doors.

Q: The title track “L.A. Woman” embodies movement, freedom, lust and dust.

A: ‘L.A. Woman’ is just a fast L.A. kick arse freeway driving song in the key of A with barely any chord changes at all. And it just goes. It’s like Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg heading from L.A. up to Bakersfield on the 5 Freeway. Let’s go, man.

Q: The haunting “Riders On The Storm.” In 1995 you ran down the song to me commenting on that highway and freeway chase depicted. “The storm is an unresolved psyche. We are moving into the Jungian collective unconscious. And those motivations in the collective unconscious are the same in 1976, 1968, 1969 as they are in 1994, 1995. There are needs that we all have on the human planet, and we must satisfy those needs and come to grips with the darkness and the interior of the human psyche.”

A: It’s the final classic, man. Interestingly, Robby and Jim come in and were working on ‘Riders On The Storm.’ And then they start to play it and it sounded like ‘An old cow poke riding out one dark and misty day.’ It was like ‘Ghost Riders in The Sky.’ No. We don’t do anything like ‘Ghost Riders In The Sky’ as much as I like it by Vaughn Monroe. And Jim likes it. What’s next? A version of Frankie Laine’s ‘Mule Train?’ Doors don’t do that. Let’s make this hip. The idea is good. We’re going to go out on the desert. ‘There’s a killer on the road.’ This has got to be dark, strange and moody. Let me see what I can do here. It was like ‘Light My Fire.’ It just came to me. I got it. The bass line. It became this dark, moody Sunset Strip 1948 jazz joint.

Q: And, only Morrison could inject a Hollywood movie studio system reference in the lyric ‘an actor out on loan.’

A: Yeah. How ‘bout that, man.

Q: Every Doors concert was unique. Some specific songs in the set but

lots of improv and no set order.

A: The concerts were an extension of the audio document. It was not yin

and yang. One was an extension of the other. There were improvisations

in the recording studio but within their soloing sections. And quite

frankly, I never knew what I was going to play. I knew the chord changes.

I didn’t know how I was going to structure my A minor 7h chord. That

would vary from take to take. It would always be an A minor 7th and in

the groove. So there was improvisation in the studio but here was major

improvisation live.

The whole Doors’ organ sound, what makes that work, that’s my whole Slavic upbringing. That’s being a ‘Polish Pianist.’ That’s that dark Slavic Stravinsky, Chopin, that great mournful Bartok type thing. Dark, mournful Slavic soul married so perfectly with the Carson McCullers American Florida southern gothic words ‘Tennessee Williams’ poetry, that the two of us went ‘Crunch!’ and the whole thing came right together perfectly. Playing with Jim, Robby and John was falling off a log. Writing those songs and inventing things.

The Doors … Each song and album has its own place. I still play the albums and can live the emotion. A lot of beautiful times went down. I think of going to UCLA, meeting Jim, meeting Dorothy Fujikawa who’s now my wife and a lot of great times.

Tat was such a fecund time as Jim said, in that year we had a great visitation of energy. That year with the Doors lasted from 1965-1971. We were just composing fools. So that was the easiest thing I’ve ever done

JOHN DENSMORE: I had to work harder on the tempo because Ray’s left hand was the bass. And when he took a solo he’d get excited and speed up. “Hold it back. Hold it back.” But, without a separate guy doing bass line runs and grooves there are holes. “OK. I’m going in.” Sometimes I didn’t do anything. That was my territory between the beats.

During band rehearsals or just before we recorded, mainly I heard Jim’s words live and by himself in the garage, or Ray would hand me a slip of paper and they were pulsating rhythms of words. Because Jim was a poet they were edited. Like, “Break On Through” was so percussive. When we were recording and locked in, I was in it. We were just so in it. We were lost. Playing live there were big sections on “The End” or “When The Music’s Over” when we would vamp, and Jim would throw in anything. And then, “Oh yeah? I’ll throw that back at you. Check this out.”

“I saw Coltrane many times. I noticed with Elvin Jones and John Coltrane there was communication. So, I thought, ‘I’m gonna keep the beat. That’s our job as drummers. But, I’m gonna try and talk to Jim during the music.’ Like, ‘When the Music’s Over.’ “What have they done to the earth….” That’s Elvin [Jones]. I knew I wasn’t playing jazz.

“With the Doors I had to work harder on the tempo because Ray’s left hand was the bass. And when he took a solo he’d get excited and speed up. ‘Hold it back. Hold it back.’ But, without a separate guy doing bass line runs and grooves there are holes. ‘OK. I’m going in.’ Sometimes I didn’t do anything. That was my territory between the beats.

"I saw Chico Hamilton at the Light House club. There was this ride cymbal riff that Chico did on a song. The ride cymbal on ‘The End’ once I get to the kit I’m playing the tambourine. It’s Chico Hamilton. That’s where it came from. Chico was direct, and going into the bridge on ‘Wild Child.’ That’s the press roll from Art Blakeley. That was direct from the records on Pacific Jazz and World Pacific.

I think nature alters your conscious. It certainly calms one’s psyche. Maybe you get more centered and you get to the essence of what you are trying to create. We took the album photo of the Doors’ ‘Waiting For The Sun’ in Laurel Canyon. It was at the top of the Canyon overlooking the city, and their wasn’t as many house, so it was a little more rural. Jim was great. This was early. Young, energetic, curious, smart guy who knew nothing about music and was real interested in how it all worked. He was cool. We used to go to Ah Fong’s a Chinese restaurant right near Sunset and Laurel Canyon. It was your typical Chinese restaurant and they would bark at you. Our 11:00 A.M. egg fried rice. You know, we wrote the first two Doors’ albums before we made any records. So Robby and I are in the Lookout Mountain house, a block down from Appian Way, and that’s where Jim walked up and wrote ‘People Are Strange’ on a matchbook.

Sunset Sound had a real echo chamber like the famous echo chamber at Capitol and it had a pocket that was fat. Just a warm fat echo chamber. You can’t buy that kind of shit. First of all when I went into Sunset Sound in the very beginning I had no clue what a good drum sound was. And I couldn’t believe you had to change the sound and kind of muffle it. Which Rothchild taught me. I loved Paul Rothchild but he got so perfectionist. He was tough but taught us so much. And mid-period, ‘Waiting For The Son’ and ‘The Soft Parade,’ he had me doing a s drum sound to tap on each drum and I’d have to do it for a fuckin’ hour. And I was exhausted. We did a 100 takes for ‘The Unknown Soldier.’

By the time we started working with Bruce Botnick at the Doors’ Workshop and in 15-20 minutes, ‘Great. Let’s go. You’ve made a lot of records and you know what a good drum sound is. I don’t have to flog you like Paul used to do.’ We did ‘L.A. Woman’ there and it was more live. And Jim was in the bathroom which was our vocal booth. We did no more than a couple of takes on everything. Just pure passion and no perfection. Strip it down to the bare raw roots.

Elektra was a good studio. My thing was that I taped my wallet to my snare drum. And then we’d go to eat and I’d leave my wallet and I didn’t have to pay for drinks. (laughs). Not on purpose. Like in the 1950’s drummers used to do that before mufflers.

Robby Krieger:

One night before we were to record, the phone rings about 4 am. I knew who it was. Jim says, ‘Robby, Pam and I took too much acid, man, you gotta come over. You gotta help us.’ I got out of bed and drove over there, fearing the worst. They were like harmless babies, not on a bummer, but more just bored, I immediately knew what to do. When on acid, always seek nature! They wanted me to take some but I refused, I said, ‘Let’s go across the street to Griffith Park. It’ll be great.’ ‘Yeah, yeah,’ they were excited. As they started out the door I said, ‘Shouldn’t you get dressed first?’ They agreed and out we went. They were freaking out, having a great time, so I figured they were okay.

I said, ‘Jim, remember we’re recording tomorrow.’ ‘I’ll be there.’ “Of course, he wasn’t. Probably asleep we assumed. What to do? Ray said, ‘let’s do the track, and leave spaces where Jim does his thing.’ We decided it was worth a try, so we laid it down, trying to imagine where Jim would come in, and other such improvisations that were different every time we played it. Finally Jim shows up eight hours late, pretending to have forgotten the 2 p.m. start…He got it in one take. Amazing!”

Q: Tell me about Paul Rothchild who had produced albums by The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Love.

A: Paul Rothchild was great. He was just what we needed, a very strong personality and real smart which Jim looked up to. And he knew a lot about recording, you know, which we knew nothing about. There are very few guys that Jim would look up to actually and the same with us. He would make us do 50 takes. Bruce Botnick our engineer for all the albums and the producer of ‘L.A. Woman’ is a little bit overlooked. He is a perfectionist. So is Paul. Bruce is the guy who actually turned the knobs and you can’t argue with the sound he got. He was very young but had produced the Supremes and a lot of stuff.

It was a blast to have Curtis Amy in the studio. That was the most fun part. You got to meet all these great musicians and hang out. They were our heroes. Like on ‘Touch Me,’ Curtis took the solo. That was the first time that happened. It served the song. That was another example of egos not getting in the way for the sake of the song. Leroy Vinegar was on our Waiting For The Son album. In fact he played on ‘Spanish Caravan,’ which was pretty silly ‘cause it wasn’t his type of forte.

The only reason we wanted a stand up bassist was that it was right for the sound and Leroy was a good reader, and it was a written part. Probably any guy could have done it. Doug Lubahn and Harvey Brooks were the bass players on The Soft Parade. Leroy was a bit taken back when he saw what we wanted to do. ‘This isn’t really my thing.’ ‘Come on, Leroy, you can do it.’ (laughs). On stage we didn’t have a bass player just the three musicians. Ray covered it. There were a couple of other groups who did that, the Seeds and Lonnie Mack. I loved Lonnie. He played on ‘Roadhouse Blues.’

Jim and I had a telepathic relationship. It was a perfect combo. That’s how you make a great group. You have three, four or five guys who come together and have that perfect intuitive relationship and stuff comes out.

When we did the first Doors’ album Jim was totally un-experienced in the studio as far as recording his vocals. He had a year with his voice playing live every night. He had never done anything in the studio. And I think by the time The Soft Parade came around his voice had matured a lot as far as low notes and range. Stuff like that. I don’t think he could have sung ‘Touch Me’ nearly as good if that was on our first album.

There was this crazy little song that I had called "Do It," and when I sang it to the guys they really liked how I sang it. ‘You sound a little like Bob Dylan. Maybe you should sing that song. And then Jim added the part about Otis Redding. That’s an example on how Jim would make my songs better. We had an ethic that we wanted to make the song better. Jim was amazing in that way. Possibly the least ego-bound songwriter I have ever worked with, no question. As far as, ‘Hey…That’s my line…’ It wasn’t like that at all. He was always open to discussion and for things I told him to sing. He wasn’t really a musician but usually what would happen is that he would come up with something better.

Q: “Wishful Sinful.”

A: It’s definitely one of my favorites on the album. The orchestration is really good. I love the chords and stuff I came up with on that song. I wish I knew how I did it. (laughs).

Q: “Wild Child.”

A: It’s one of my favorites because it’s live. That one didn’t need strings or horns. The title song ‘The Soft Parade’ was quite a work. It was actually three songs in one.

We didn’t tour the The Soft Parade album. We only did it twice. It was another step for the Doors to try something different. The reason I didn’t like it was that I felt we were kind of doing the album for somebody else. But I definitely like how it came out, you know. A couple of years later we tried re-mixing some stuff without the strings and horns but it didn’t quite work. We had actually tailored the arrangements to horns and strings and to put that out again would be a lot of work, or alter the arrangements.

Bruce Botnick Engineer / Producer

Los Angeles native Bruce Botnick, is a sound engineer and record producer. At age 18 he talked his way into a job at Liberty Records in Hollywood where he subsequently recorded Bobby Vee, Johnny Burnette, Jackie DeShannon, Leon Russell, David Gates and with arranger Jack Nitzsche.

Botnick then moved to Sunset Sound, hired as a mixer initially to do children’s albums for Disney.

Then the Doors walked in off the street into the fabled Sunset Sound facility with their producer, Paul A. Rothchild, an A&R signing courtesy of Elektra Records’ founder and owner, Jac Holzman.

Botnick is acclaimed for engineering the entire Doors’ recording catalogue as well as engineering Love’s first two albums. He also produced their seminal Forever Changes LP. in 1967. He co-produced the Doors’ L.A. Woman.

Bruce was at the dials at several epic rock ‘n’ roll special moments: “Here Today” from Brian Wilson’s Pet Sounds, Buffalo Springfield’s “Blue Bird” and “Expecting To Fly,” and a credit as an assistant engineer to Glyn Johns on the “Gimme Shelter” session on the Rolling Stones’ Let It Bleed.

Q: So many incredible albums were recorded at Sunset Sound in Hollywood on Sunset Blvd. Love, Doors, Buffalo Springfield, the Rolling Stones mixed Beggar’s Banquet, and Exile On Main Street in the facility. Tell me about the studio and the magic of the atmosphere.

A: It was built by a man named Alan Emig, who had come from Columbia Records. He was a well-known mixer there and designed a custom built 14 in put tune console for Sunset Sound.

Salvador “Tutti” Camarata, a trumpet player originally and an arranger, and did big band stuff in the 1940s and ‘50s had a friendship with Disney and decided to build a recording studio to handle the Disney records and all the movies, “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.” On a normal day we’d go from 8:00 AM to 9:30 PM with commercials.

Q: You worked a bit earlier with arranger and musician, Jack Nitzsche on records by Bobby Vee and Jackie De Shannon.

A: He came into the picture early on when I was doing work for Liberty Records, which is where I came from. Jack was the arranger on a Bobby Vee date. Jack was the arranger and liked what he heard. He had been working over at RCA and at Gold Star doing a lot of recording. He started bringing tons of stuff in.

And right in the middle of that relationship with Jack, the Doors walked through the door. I had already done Love before that. And the Doors came in the door with (producer) Paul (Rothchild. Knowing that in between the first Love album and the first Doors album was the first Tim Buckley album. And that was the first album that Paul Rothchild had done since he had gotten out of jail for a trumped up government charge on marijuana, where they had sent him stuff in the mail. And he opened the box. ‘My goodness. Look at this. Where did this come from?’ And the next thing was the doorbell rang and there was the Drug Enforcement Agency.

Q: At Sunset Sound, what did the room bring to the recordings you engineered or produced?

A: Well, the room was very unique. Tuti Camarata did something that nobody had done in this country. He built an isolation booth for the vocals. And later on I convinced him to take the mono disc mastering system and move it into the back behind what became studio 2. And we turned that into a very large isolation booth which we used to put stings in. That’s one of the things that worked so well for Jack Nitzsche because we were able to put six strings in there and get full isolation live. It was great.

With the strings being in the large isolation booth the drums didn’t suffer so we were able to make tighter and punchier rhythm tracks than any of the other studios in town were able to do. ‘Cause everybody did everything live in those days. You did your vocals live. You did your strings and your brass live. And the rhythm section. And this was a big deal. And then add to it the amazing echo chamber that Alan Emig designed. Still phenomenal and having survived a fire. It still sounds incredible.

Microphones and placement. All different microphones have different coloration and different sounds. And, if you have a good selection, like we did at Sunset Sound, it was all tubes, except for some Ribbon, RCA’s and a few Dynamics, they were all tube microphones. U-47’s, Sony.

And we picked the microphone depending on the sound we were trying to get. And that was part of the palate. I still take that approach to this day. And by choosing the right microphone and putting it in the right place, a lot of times you can avoid having to EQ it.

Q: What astounds you many decades later listening to your collaboration with Paul Rothchild and the Doors?

A: The thing that still works for me is, first and foremost, the music. The musicianship. The performance. And all of those when these guys connected as a unit and became unconscious is good or better than anything I’ve ever heard. I was just working on a score that I had recorded with Jerry Goldsmith on a movie called First Night. And it’s extraordinary because a good half of the album the 110 musicians were totally un-conscious and the performances spectacular. And that’s one of the things I have to hand to my friend producer Paul Rothchild. That we went for performance and tried to stay out of it not to become too technically in the front of the albums that were manufactured.

In the case of the Doors, Paul was the man who drove the train and kept it on the tracks. But the reality is that there were six of us in the studio making these records together. And it wasn’t a matter of one person “being the person.” Paul never took that point. At some point during the relationship and especially when Jim got busted in Miami, where Paul had to step up and take more control. Because somebody had too or otherwise it would have never got done. But generally his approach was to get the performance. And we weren’t afraid of editing between takes. You get an amazing first verse and second verse and a chorus and verse into the bridge and it would sort of fall apart and we would grab another take that had it and edited it all together. And it was about the performance. It wasn’t about overdubbing. Because in the majority of what the Doors played on their records was played live.

ou have to realize that when Buffalo Springfield came into the studio they were rehearsed. They had played their music live. Double sets at night clubs. Same thing as the Doors. That’s one of the reasons we were able to get good performances.

Jac Holzman: Founder Elektra Records

As for the debut Doors’ album, [producer] Paul Rothchild and I discussed how far we should take ‘em. He said, ‘Well, why don’t we take them to 80 per cent of concert pitch and let them come in the studio.’ ‘That sounds great to me.’ So that’s what we did.

Jim and Arthur Lee were interesting characters. Jim Morrison died young. Jimmy Dean. That’s part of it. But Jim lived his life as full and he lived his life without any attention to convention, or what anybody else thought and a flame that bright usually does not burn long.

Arthur admired the Doors. And he was the one who said you ought to stay around for their Whisky a Go Go show. ‘That band is pretty good.’

Now I stay around for the Doors’ show in March of 1966. When I saw them I heard a lot of blues and I didn’t need any more white blues singers. And the band did not feel that comfortable. The Doors could do the blues but it was later when I heard the adventurous of their approach of taking something like ‘The Alabama Song’ and converting it so it could be done as a rock-infused song. That told me a lot.

I was more impressed by Ray Manzarek at the beginning than I was by Jim. Jim had the vocal chops but that personae crept out once he knew he had a safe home or a safe perch to work from.

Remember: The Doors were a band that had been signed to Columbia [Records] and they couldn’t even get to make a single. And the reason I offered them a three-album guarantee was that I never wanted them to feel that they would get booted out the door if the first LP didn’t sell. So that was the genesis of that. ‘What can I do that nobody else is crazy enough to do?’

There were two Doors albums out in 1967. Which was unusual but it was done on purpose to get them really established as an act and not as a one album wonder. So we had the first album that came out in January and then we had Strange Days which came out in October, and recorded in summer.”

My part of the creative process is to be involved but not buried in the middle to the extent that I lost my perception or position to be able to look at it from slightly afar. So as to determine what we got was what I thought was going to work. And album covers were important to the sale of music.

I saw myself as a mid-wife to their music. They recorded it. I helped supervise how it was going to be taken in and what I hoped would be willing ears. That’s my job. And it’s my job to talk tough when I need too. But I never had that kind of problem with the Doors.

The only time was when there was much screaming about Miami. I said, ‘if your shows are being cancelled we will figure something out about how we’re going to bring you back live. In the meantime, go into the studio and start writing another album.’ And that was Morrison Hotel.

And then we did two evenings of Doors’ concerts at the Aquarius Theater on Sunset Blvd. and those tickets were two dollars. We underwrote the rest. We picked up the tab. But it was there where we launched them. And that idea came from us. That’s kind of what you do when you live your artists anguish and you try and help them and you over the tough spots.

Dave Diamond: KBLA Deejay

I saw the Doors at The London Fog and the Whisky a Go Go. I played The Doors LP acetate on my KBLA Diamond Mine show. The Doors did a couple of high school gigs for me. I spun selections from their album along with numerous tracks from Love. In early 1966 I had telephoned Jac Holzman and mentioned the Doors to him.

“Break on Through” their first single, really didn’t make it. Robby [Krieger] and John [Densmore] come over to my Los Feliz place, checking my fan mail and reading all the letters [that said,] ‘Play the Doors!’ I’d get fifty or sixty letters a day, ’cause I was spinning this new stuff. People were just going nuts. They never had heard this kind of music.

One day, they come over, and they are both all sullen and gloom. ‘Break on Through’ stiffed. We don’t know what to do, and the record company won’t do this and that.’ I said, ‘Have them put out ‘Light My Fire.’’ They replied, ‘They won’t do it because it’s too long. No one will play that long a record.’

So I took them over to KBLA and showed them how to edit it down, removing the long instrumental passage. ‘Take that to Jac Holzman, and you’ll have a number-one hit.’ And that’s what they did.

Guy Webster: Photographer

On my first shooting with the Doors they were very easy to work with. Because it was their first real formal photo session for their album and they didn’t know what to expect.

I didn’t recognize any of them particularly. Until Jim (Morrison) said something. Jim and I sat near each other in class in philosophy at UCLA. We recognized each other every day and would nod. But I did not recognize him when he came into my photo studio for the very first session in 1966 the day after I saw the Doors perform at the Whisky A Go Go.

His appearance had changed a lot from UCLA. He must have lost at least 30 pounds and grew his hair longer since 1965. He’s the one who said to me when I first greeted him at my studio. “Hey Guy. We were in class together at UCLA.” Oh my God! Then I realized who he was. At UCLA we talked very little. It was a quarter system and really hard. It was just reviewing the stuff we read the night before by the professor. Nobody really talked in the class to one another.

Morrison had the ability to project larger on stage and in photos. It wasn’t a thing where his persona made him bigger in photos or on the concert stage. He might have been five foot nine but was trim and his body was in very good shape. That’s why I had him take his shirt off for one of the shots. And his hair looked nice. I knew very early in working with him on that initial shoot he had a sense of photography and visuals. I think what really happened was that he trusted me and then when I did that shot of him that made him esoteric and ethereal. He went with it. I wanted something ethereal and he gave it to me. The other members of the Doors never took their shirts off and stayed in character as musicians.

Here’s the deal on Jim taking his shirt off for the photo session. Once we realized that we were in school together and that I was already famous with my album covers, I said, “Look Jim. You’re wearing this shirt and it’s embarrassing because it has ribbons on it. I know it’s a hippie shirt but you can buy it in Venice Beach and you can buy it anywhere.” And it would have dated him. “I’m gonna take your shirt off. You’ll be alright. Trust me. And I’m gonna make you look like Jesus Christ.” And that’s what it was.

I put Jim’s face forward and I designed the front cover of their debut LP and put the other three guys as his eyes and part of his brain. But I made Jim the star on purpose ’cause I knew it could sell the album.

Jac Holzman liked it and put that on the cover. He always let me do what I wanted for the cover.

But I never thought of Jim as a great singer. He had the emotion. He got into it. I met every great singer years before I heard the Doors. Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin. Jim could get the emotion across and convey everything. Absolutely. He had the ability to tap into the meaning of things he was singing. I thought he was brilliant. But remember-there were a lot of detractors, you know. Everyone didn’t like the Doors initially. There was a split group in L.A. But I loved them.

Once the Doors hit it big, we really didn’t do a whole lot of talking or communicating. We’d go out on location and get it done. I shot the back cover photo on a hill where I did silhouettes of them for their Waiting For The Sun album. That was fun.

And the 1968 session around ‘Unknown Soldier” at the Westwood cemetery. By then Jim had changed. He didn’t look as healthy and his hair was groomed properly. I didn’t really look at the photo of Jim in the cemetery again until after he died. I realized it was kind of a requiem for Jim himself.

It was raining and very hard to take pictures without getting ugly buildings in the background. The one image on my website has Jim on the side. I was worried about putting it out there because it was too macabre so I didn’t push that photo. I loved the Vietnam commentary being done in front of me. Anything that was political+. Jim Morrison had a sense of fashion. He understood. He was super educated, even though he educated himself, going to UCLA at that time in the mid-sixties after transferring from a university in Florida.

In 1971 I was taking pictures of Natalie Wood. She was like a friend of ours, because my first wife and I were very close to Natalie and her husband, Richard Gregson. And I was friends with her. And she said, “Will you do some pictures for me.” “Absolutely.”

So we went up to Malibu, to Serra Retreat, and we were shooting there. Not too many cars and she wouldn’t be bothered. And this limousine pulled up and the window came down. And this burly 250 pound man with a full beard and hair said, “Guy.” “Who is it?” “Jim.” “Jim Morrison?” I didn’t recognize him. He asked, “What are you doing?” “Well, I’m just finishing up some work and then I’m moving to Spain and I’ll be there for quite a while.” And he said he was moving to France in the next week.” And I said, “Well, shit, we gotta get in touch.” And that was the last time I saw him…I moved to Spain and he moved to France and he died a couple of months later.

Kim Fowley: Record Producer/Songwriter

I saw the Doors at Ciro’s on Sunset Blvd. and everywhere. I introduced them at the Devonshire Downs Meadows Raceway in Northridge at Valley State College in July1967. It was the Fantasy Faire & Magic Music Festival. Astounding. They had magic. In 1969 I introduced them on stage in Canada at the Toronto Pop Festival where John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band appeared.

Jim could sing in pitch. He had the image and the poetry. He understood theater. Ray’s organ was a music box to a volcano. Manzarek supplied a pulse, and Robby the guitarist is never given credit what he brought to the table in 1967. John Densmore was a jazz drummer. You also had a jazz keyboardist and a jazz guitarist all playing the blues with a real great poet and actor fronting it. It was tremendous. It was theater.

Jim Morrison was the best white person performer. Better than Elvis. Better than Jagger. Because he did what Howlin’ Wolf and Lawrence Olivier did. Morrison did it all at the same time. He did William Shakespeare and gut bucket together. And only PJ Proby rivaled him and David Bowie came in third.

The Doors were not a rock ‘n’ roll band but gave you a rock ‘n’ roll feeling. And the only band that did that was the original King Crimson. ‘Cause they weren’t a rock ‘n’ roll band, either. But when you heard Court of the Crimson King, and Pink Floyd ’67, they were the only bands who had some Wagner with a rock ‘n’ roll attitude.

Marty Balin: Jefferson Airplane

Q: In 1965, you opened the Matrix club in San Francisco. The Doors played the Matrix club in very early 1967. I know in ’67 and 1968 you toured the US and Europe together.

A: I didn’t see the Doors at the Matrix Club but saw them many times. We worked and played with them many times in 1967 and ’68. We did some high school and college shows together and toured Europe.

I loved the Doors. Oh my God! I thought Jim Morrison was fantastic. I fortunately became a friend and hung out and got to drink with him. He’d read me his poems all the time. I thought that was funny. I thought Jim was great as an artist. Who knows? He would have probably gone into film and done movies. The guy was a good lookin’ dude, man. I’d go out with him and try and pick up chicks and I was like invisible.

Carlos Santana

Q: Your autobiography The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story to Light really details the impact the new 1967 FM underground rock radio had on you in Sam Francisco.

A: It blew my mind when I found KSAN-FM radio station. They played the whole songs of Vanilla Fudge, Country Joe & The Fish, the long version of Traffic’s “Smiling Phases,’ the long version of ‘Light My Fire.’ ‘Wow. This is really, really cool.’ Taking LSD and listening to Frank Zappa.

I’m very grateful that my timing with my mom and dad was perfect in being in San Francisco when it all hit: The Doors, Grateful Dead, Ravi Shankar. Coltrane. There was an explosion of consciousness that made you question authority. Black power, rainbow power.

The only thing the Santana band never wanted to do was succumb to phony. We were watching what was all unfolding with Sly Stone and Jim Morrison and it was becoming too much for all of them. Becoming victims of an avalanche of illusion by not being prepared mentality to not deal with mass quantity adulation. I’m not dependent or addicted to mass adulation. That stuff makes me feel uncomfortable. I’m not afraid of it. I have learned to balance it.

Henry Diltz: Photographer

Q: You knew the Doors and did the album cover photo for their “Morrison Hotel” LP. What attracted you to them?

A: They were interesting and weren’t a guitar band. They came from a different place. It was that keyboard thing. They didn’t have a bass. Ray Manzarek played bass on a keyboard with his left hand. It was a little more classical and jazz-oriented. And then you had (Jim) Morrison singing those words with that baritone voice. It was poetic and more like a beatnik thing. It was different. And Jim wrote all those deep lyrics. I took photos of them at The Hollywood Bowl in 1968 when they did a concert.

Jim lived in Laurel Canyon. So did Robby (Krieger) and John Densmore. We were all friends in the area. I knew him as a musician just as I was first really taking photos. I did one day with the Doors in downtown L.A. for Morrison Hotel and got that picture. Then two days later they needed some black and white publicity pictures and we walked around the beach in Venice.

Q: Your Venice beach photos have become the image for their recent When You’re Strange film.

A: Here’s the thing. I shot about 8 rolls of film that day of them in Venice. Over the years, 6 or 8 of them have become the ones we printed and offered for sales in our gallery. ‘Here’s the beautiful one. Here’s the great one. Everyone looks good in this shot.’ You might look at 6 or 8 in a row and you pick the best one. Someone’s eyes are closed in this one. One guy is not looking at the camera. And you pick the one that is great. And that becomes the famous one. Well, somebody at Rhino and the Doors’ outfit looked at the proof sheets and found one that did not fit that category. Sort of an outtake.

I never printed it because Jim is not looking at the camera. They are walking and it’s not real sharp. But they picked that one and there is something about it. It’s random, see. I always picked the ones that look iconic. But really, maybe those random ones in between are kind of more interesting now.

Q: Do you have a theory why the music of The Doors and Laurel Canyon, a region where you lived in 1965-1975 became popular and why the music from that area still resonates?

A: It was the flowering and the renaissance of the singer/songwriter. I think it had a lot to do with that change that it came from folk music. And then they started putting their own lyrics into it. And, smoking grass had a hell of a lot to do with it. Smoking grass had everything to do with the whole ‘60s thing. Long hair, hippies, peace and love, because that’s the way it makes you feel. And love beads and the music. Smoking a little grass makes you very thoughtful and increases your feeling and focus on things. You start thinking about trying to put thoughts into words and songs.

Tony Funches: Jim Morrison’s Bodyguard and Confident

Q: You were with Jim and the Doors for eleven months during 1970-1971.

A: Jim had his scene down. An apartment on West Norton Ave., the Doors’ office, the Alta-Cienega motel, and Elektra Records on Santa Monica Blvd. and La Cienega Blvd. All stumbling distance from each other. [Laughs]. All within two or three blocks.

Q: You were at the Doors’ office in April 1970 and saw Jim Morrison’s The Lords and New Creatures when a box of poetry books arrived.

A: I had a copy Jim autographed and gave to me but I lost it. Yeah…That was so cool. That was so fuckin’ cool. On that particular day I had no specific real duties to perform other than I just happened to be there. Jim was really excited. Everybody was. All of his band mates and all of the Doors family as it were just really happy for him. An incredible festive moment that wasn’t real done in a formal sense. The cases of the books arrived and everybody went, ‘Hey Jim. Your books are here.’ Low key. Jim was like real shy about opening it up and he was trying to hide how proud he was because this was a step to legitimacy as a poet and after we opened the first case of books, everyday said, ‘Fuck it, man, let’s party.’ I thoroughly enjoyed the occasion of seeing him that happy. Unbridled pure happiness. Not with sticking his chest out getting all stupid, the quiet happiness of seeing oneself validated. So that was so fuckin’ special.

I know that there was some drama in Simon & Shuster finally winding up as the publisher. There was intense drama associated with that. Jim was really a humble guy and almost apologetically so. He cared about such things that others would recognize if not his talent his efforts to be an artist. That’s why the Lizard King, bull shit teeny bopper shit that drove him up the wall.

Q: The Doors and Albert King played the Long Beach Arena in 1970.

A: I went to get Jim for the show. He was staying at the Alta Cienega. When I knocked on the door he said he was working on a poem and he would be at the concert…I believed him, and a few minutes before the concert up pulls a cab and Jim is in it.

Jim had the artistic bent that allowed him given his rebelliousness and the idiom he was expressing himself threw to do that improvisation in live performances or on records. He did that in his artistic expressions because that capability was resident within his personality. While at the same time he drew comfort in knowing that others had been doing similar things as with Cab Calloway doing scat singing with the Zoot suit or Bobby Darin when he did ‘Mack the Knife.’ So he knew of those things but he did not do them as they did but he was aware that others had improvised similarly and since they had, he figured, ‘I’m gonna give it a try. But I can’t do what they do.’ So he did what he did according to what made him tick which made it separate but not equal. But separate.

It wasn’t up to me to be Jim’s nanny. You could influence him as best you can. If Jim decided to get stoned or stinkin’ drunk before a gig sometimes I could head that off and other times...I didn’t live with the cat for 24 7, ya know. I was at home in Venice. He’s gonna do what he was gonna do. We did a little bit of telephone, had meals. We both ate meat and potatoes. Jim had a house as well on Kings Road. I went there once or twice, the mysterious house that he got into for tax purposes. He had a few crates and boxes.

One time I went with Jim to see his accountant, Bob Greene. The Doors were protected. They completely managed themselves. But they had extra advice from excellent people. Jim really didn’t see himself as a participatory mogul in the business of the Doors. But since he had come up with the idea of it being a through democracy at certain times he had to show up and participate. It was his idea and he couldn’t very well just say, ‘you guys go ahead I’ll sit it out.’ And they’d remind him of that. ‘You gotta show up.’ As soon as he could weasel out of the official duties, he’d say, ‘come on, man, let’s go get a drink over at the Phone Booth. He never carried cash. The accountant always made sure I had five grand. Jim could be so comical. Kind of like a kid. He had his Diner’s Club card. He had two or three credit cards and he got in the habit of remembering to carry them. And he used them exclusively. All of those transactions went straight to his accountant’s office who took care of them. Jim never knew how much money he had. He was a millionaire and didn’t know it.

Q: You were in Dade County, Miami in 1970 for Morrison’s trial where he was charged with a felony count of lewd and lascivious behavior and indecent exposure when the guilty verdict was read. In 2011, the outgoing Governor Charlie Crist pardoned Jim Morrison in the indecent-exposure case against him.